Study on Professional Outpatient Preventative Dentistry (POPD)

Can it be done safely and effectively without the use of general anesthesia?

By Mayra Urbieta, DMD, Stephanie Sur, DVM, Patrick Hardigan, PhD, Darren Pike, DMD, MS and Chad Orlich, DMD

A double-blind study of 12 dogs and 12 cats, randomly selected and divided by age group and history of anesthetic dental treatment, were used in the study. Subjects were treated with an experimental intervention (POPD) by a trained Pet Dental Services (PDS) technician and subsequently examined under general anesthesia by a board-certifi ed veterinary dentist (control). The examination consisted of inspection for any remaining subgingival calculus using compressed air, exposed full mouth radiographs and a complete oral exam. Parameters examined by both groups included recession, furcation, hyperplasia, resorption, missing teeth, fractures/attrition/ abrasion, supernumerary teeth, and probing depths.

Results showed that the trained technicians and the veterinary dentist were both able to identify the seven dental conditions, although the technician appeared to report more pathology. After the POPD was successfully completed, no residual plaque or calculus was detected on any of the dogs or cats and there were no post-treatment complications. Although a POPD is not intended to be a substitute for anesthetic dentistry, it may prove to be a valuable supplemental treatment. The methods for the study included fi rst grouping the 24 animals by age and prior dentistry within the preceding two years. All were examined by a board certifi ed veterinary dentist to determine the appropriateness of a POPD, and evaluated with lab work to determine eligibility for general anesthesia. All subjects were deemed to be healthy and capable of undergoing the procedures required for this trial. The experimental intervention (POPD) was performed on all patients by PDS technicians who are qualifi ed by examination from the American Society of Veterinary Dental Technicians (ASVDT), First Aid/CPR certifi ed by the American Red Cross, and with a minimum of three years of experience working in a veterinary hospital. They were instructed over a six-month period, with a training program developed in part by a boardcertifi ed periodontist and PDS, and overseen by multiple veterinarians.

Results showed that the trained technicians and the veterinary dentist were both able to identify the seven dental conditions, although the technician appeared to report more pathology. After the POPD was successfully completed, no residual plaque or calculus was detected on any of the dogs or cats and there were no post-treatment complications. Although a POPD is not intended to be a substitute for anesthetic dentistry, it may prove to be a valuable supplemental treatment. The methods for the study included fi rst grouping the 24 animals by age and prior dentistry within the preceding two years. All were examined by a board certifi ed veterinary dentist to determine the appropriateness of a POPD, and evaluated with lab work to determine eligibility for general anesthesia. All subjects were deemed to be healthy and capable of undergoing the procedures required for this trial. The experimental intervention (POPD) was performed on all patients by PDS technicians who are qualifi ed by examination from the American Society of Veterinary Dental Technicians (ASVDT), First Aid/CPR certifi ed by the American Red Cross, and with a minimum of three years of experience working in a veterinary hospital. They were instructed over a six-month period, with a training program developed in part by a boardcertifi ed periodontist and PDS, and overseen by multiple veterinarians.

The POPD 11-step protocol used by PDS technicians follows; however, steps 3, 10 and 11 were omitted in order to maintain the double-blind study design.

STEP 1: Medical and behavioral history check.

STEP 2: Pre-exam – physical and oral. A check of joint discomfort or pain is conducted to determine a pet’s candidacy for the procedure since restraint is necessary during a POPD. A complete extra-oral and intra-oral exam is completed, with a specific focus on tooth symmetry, swelling and pain. An evaluation is also performed on each tooth, and surrounding gingiva, for pathology including calculus levels, compromised teeth, gingival condition and periodontal pockets. At this point, in a clinic setting, for 62.5% of the subjects, the technician would have stopped the procedure after the exam and discussed the findings with the veterinarian because he/she would be recommending an anesthetic dental treatment.

STEP 3: Treatment plan – a treatment plan is then generated through a staff-doctor-client partnership. Treatment plans can range from simply completing the POPD procedure to recommending that the professional oral hygiene procedure be performed under general anesthesia. The treatment plans include home care instructions and a recall date for an anesthetic dental treatment or a maintenance POPD procedure, if necessary. This step is crucial in ensuring the patient receives the proper care for his/her periodontal and health condition.

STEP 4: Supra-gingival scaling – a POPD begins with the removal of supra-gingival deposits of plaque and calculus from the buccal, lingual and interproximal surfaces. A combination of forceps, hand instruments and ultrasonic piezo scaling are used for plaque and calculus removal.

STEP 5: Sub-gingival scaling and curettage – plaque and calculus deposits are thoroughly removed from the sub-gingival areas. This procedure is not performed on a patient with stage three or four periodontal disease. This reinforces the need for a pre-examination (Step 2) for patient candidacy.

STEP 6: Post dental probing – a six-point probing of each tooth is performed. A thorough probing is vital for recognizing and communicating areas of concern to the doctors and clients. All abnormal pocket depths are noted for the final chart.

STEP 7: Machine polish – hygienists then perform a machine polish using a pumice or polishing paste. Polishing will assist in smoothing out minor defects of the enamel which may have occurred during the procedure, thus aiding in the prevention of future plaque accumulation. It will also help with the removal of certain enamel stains.

STEP 8: Oral rinse – any diseased tissue, plaque or paste remnants are removed through an irrigation of the oral cavity. The oral cavity and gingival pockets or sulcus are flushed with a chlorhexidine-based solution. 36 IVC Fall 2013

STEP 9: Post-check and charting – a complete evaluation of each tooth is performed, checking for any retained calculus with a periodontal probe and/or explorer. The dental chart is completed.

STEP 10: Veterinarian and staff communication – a veterinarian examines the oral cavity with a corresponding evaluation of the dental chart to ensure complete pathological notation. A posttreatment oral health care plan is prepared for the patient.

STEP 11: Client education – fi nally, the hygienist educates clients about the importance of maintaining good oral health in their pets. They will also review the pet’s dental experience and chart, review the importance of continuous recalls and explain to them the many options regarding home care. They also provide brushing demonstrations with their pet, when necessary.

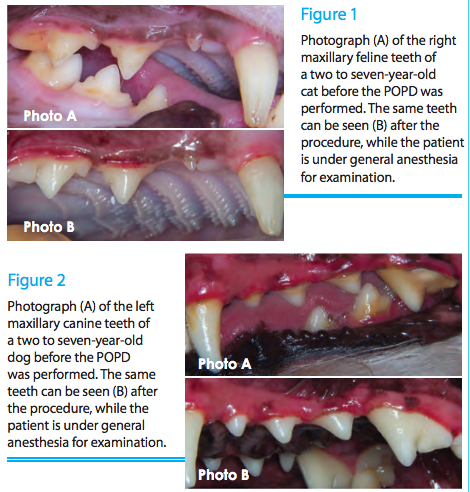

Following the completion of POPD treatment by the trained technician, all patients were immediately put under general anesthesia and examined thoroughly by a veterinarian. The veterinarian used compressed air to dry the gingival margins and properly inspect for any remaining subgingival calculus, exposed full mouth radiographs, and fi lled out a pre-designated chart. The same chart was used by the veterinarian for their pre-treatment examination. Also noted was gingival recession, furcation involvement, gingival hyperplasia, tooth resorption, missing teeth, supernumerary teeth, fractures/attrition/abrasion, and probing depths. The veterinary staff also took before and after pictures of each patient (See Figures 1 and 2 below for examples). All the patients for which the technician recommended anesthetic dental treatment were found to have radiographic fi ndings by the control group’s examination.

Following the completion of POPD treatment by the trained technician, all patients were immediately put under general anesthesia and examined thoroughly by a veterinarian. The veterinarian used compressed air to dry the gingival margins and properly inspect for any remaining subgingival calculus, exposed full mouth radiographs, and fi lled out a pre-designated chart. The same chart was used by the veterinarian for their pre-treatment examination. Also noted was gingival recession, furcation involvement, gingival hyperplasia, tooth resorption, missing teeth, supernumerary teeth, fractures/attrition/abrasion, and probing depths. The veterinary staff also took before and after pictures of each patient (See Figures 1 and 2 below for examples). All the patients for which the technician recommended anesthetic dental treatment were found to have radiographic fi ndings by the control group’s examination.

Discussion

Since plaque is the initiating cause of gingivitis and subsequent periodontitis, assessment of plaque reduction is a key step in determining the effi cacy of canine and feline dental health products and procedures. The present pilot study implies that performing a dental prophylaxis on a cat or dog without the use of general anesthesia can be done in a safe and effi cient manner by an appropriately trained technician. Not only were the dental prophylaxes completed on all 24 patients, but also there was no residual calculus remaining supra- or sub-gingivally upon thorough inspection by the veterinarian. In addition, there were no post-treatment complications, which again attest to the possibility of performing such a procedure in a safe manner. This procedure must be performed under the supervision of a licensed veterinarian. Therefore, it is crucial to keep in mind the scope of a procedure such as POPD. Like any other procedure performed by an auxiliary, POPD is to be used at the discretion of the veterinarian, for he or she is ultimately responsible for the overall health of each patient. It is not intended at any time to replace anesthetic dentistry, but to support it, meaning that it is up to the doctor to decide when and for what patients the service is appropriate. Also, it should be noted that if this were not a research setting, the technician would have stopped the POPD after the exam in 62.5% of the patients, all of which were also found to have radiographic fi ndings, and discussed the fi ndings with the veterinarian due to the nature of the present pathology.